Planning within impactful teams

When it comes to creating impact, an Engineering team has two responsibilities: to participate in discovery, the identification of opportunities that will contribute positively to the company's revenues, and delivery, the ability to produce solutions to respond to these opportunities.

The two are inextricably linked: a team that is excellent at delivery or discovery, but mediocre at the other, will have a more limited impact than one that does both well.

A team that is mediocre at delivery or discovery may even have a negative impact.

I'd like to focus on an important aspect of delivery: planning.

Delivery: the challenge of predictability

Engineering is responsible for delivery. This covers the entire activity of making a new product available, or improving an existing one.

Obviously, by the whole activity, I mean development, but not only: testing, documentation, industrialization (the famous reliability, security, scalability, performance).

An efficient team is therefore one that is capable not only of carrying out development, but also of making it available, and this within constraints: a time constraint or a budget constraint, the famous project management triangle.

But what also characterizes an effective team is its ability to plan these increments over time.

These iterations do not live independently of each other, and above all the product does not live in isolation from other teams.

For example, a general communication plan may be needed to accompany the release of an innovation.

Or the legal department may have an obligation to meet by a fixed date, etc...

In short, we have dependencies between several teams and therefore additional constraints, which increases the importance of dates.

From here, we begin to touch on a sensitive subject in IT: predictability and therefore planning.

But before we go any further on the subject of predictability, let's first distinguish between a project and a product, because the notion of predictability is not approached in the same way in both cases.

Project and product teams seek to predict different things

A project starts when we have a defined solution for a given problem. This solution is fixed by strong constraints on the "scope", i.e. the service to be rendered.

The solution, the how, is therefore :

- either fixed upstream by an external constraint, a customer need, a legal constraint, or

- or set top-down by internal decision-makers.

Project examples:

- the implementation of RGPD compliance in 2018.

- ISO 27001 certification

- the opening of a new market

- the start of a partnership

- updating a technical component of the application

- integrating your product with an ERP system

- etc.

In all the above cases, the solution has been defined. The challenge is to bring the project to fruition.

This doesn't mean that everything is set in stone - adaptations can be made - but on the whole, the path is marked out, and there's little innovation to be expected.

Conversely, when you're working on a product, the solutions aren't defined. **But the objectives are defined.

For example, a Product team will seek to improve the acquisition of new users, or their retention, or their ability to spend more etc...

There's a fundamental difference here between being in a product-driven company and a project-driven company.

Both will not seek the same kind of predictability, and will not plan in the same way.

In one case, the aim is to predict the completion time for a list of features. In the other, we're looking to anticipate the outcome of initiatives on a business objective.

The difference is sometimes subtle. In fact, a product team may give the appearance of carrying out projects. For example, it may decide to implement feature X to achieve result Y.

The subtlety lies in the fact that the product team realizes feature X to obtain result Y and will continue to work in this direction until the expected result is achieved.

This subtlety is important:

- A small piece of feature X may be enough to achieve the objective, and the team may decide to settle for a partial solution.

- If the result is not achieved, the team may decide to remove what has been tested altogether.

- The team may discover along the way that another feature Z would be more useful for achieving the result, and implement a different solution from the one initially envisaged.

Note that Marty Cagan uses a different vocabulary and speaks of "Features teams/Delivery teams" as opposed to "Impact Teams" to refer to Project teams and Product teams respectively.

TIP

Of course, a product team also has projects to manage. The examples given above can be applied to a Product team.

Agencies versus companies Product

Let's be clear: it's perfectly possible to work mainly on projects defined in advance and guided by fixed dates.

This is, for example, what all agencies (consultancies, ESN, web agencies) do, and it's normal.

Day-to-day agency work involves committing to customer needs, negotiating a scope of work to be produced by a fixed date.

It's a very difficult exercise. The best agencies sell their project management methodology at a very high price.

The available pool of people is constantly on the move, and we have to anticipate in order to assign them to the various projects that come our way.

To successfully plan a project and its dependencies, it takes a phenomenal amount of work to list all the tasks involved in a project, estimate the completion time for each of them, mobilizing dozens of people in the process, and materialize the dependencies in the form of a Gantt chart - in short, capacity planning.

An absent person, a technological imponderable - in short, a single grain of sand and everything can go wrong. These methodologies list the risks and mitigate them, by doubling the number of people needed, working on contingency plans, etc.

And to show just how complex it is, the "Standish Group Chaos report" continues to measure year after year that only 30% of IT projects are delivered on time and on budget, while 20% of these projects are complete failures. To which I'd add that I'd be curious to know which of these 30% of successful projects had the expected business impact at the outset.

Because, while this preparation phase and the time needed to coordinate it all is very expensive, it's also highly risky. Predicting the business value of a feature in advance is illusory, predicting that it will always be the most important thing to do in 6 months' time is highly optimistic, and estimating the time it will take to complete is at best a mirage.

From a "project" point of view, the biggest flaw is that it's output-oriented (functionalities), not outcome-oriented (results). So even if the objective isn't achieved, we move on to the next thing. What we're celebrating here is having delivered x or y, but without benefiting the company that purchased the service.

For my part, I'm writing this e-book for Product teams, and the best Product teams operate differently, so I won't dwell on the techniques needed to run a team that works predominantly in "agency" mode (or delivery team mode, to use Marty Cagan's terms).

For a product company, it makes no sense to celebrate the end of project X when the underlying business objective has not been met.As much as it's simple to "predict" that the GDPR compliance project will bring us into compliance, predicting that feature project Y will effectively increase the bottom line by Z% is an illusion.

In contrast, a Product company will constantly test hypotheses, apply, measure and iterate to satisfy a given objective.In other words, successful Product companies focus primarily on producing results versus listing successfully implemented features.

TIP

The difference between a product culture and a project culture is very significant. During recruitment, this is something to bear in mind when you're involved in hiring people from agencies (consulting etc...). You can of course find excellent people to join you, but you have to make sure you explain your culture. There's a lot of educational work to be done to ensure that these people don't tend towards the project mode. The product culture, which leads to regular testing and iteration, may seem too chaotic to them, and they will seek to bring in "classic" project management methods to provide more predictability.

All this brings us to one of the most divisive tools and the focus of all conflicts: the Roadmap.

The roadmap, crystallizing the differences between Product and Project

The roadmap is a communication tool designed to show the strategy in place.

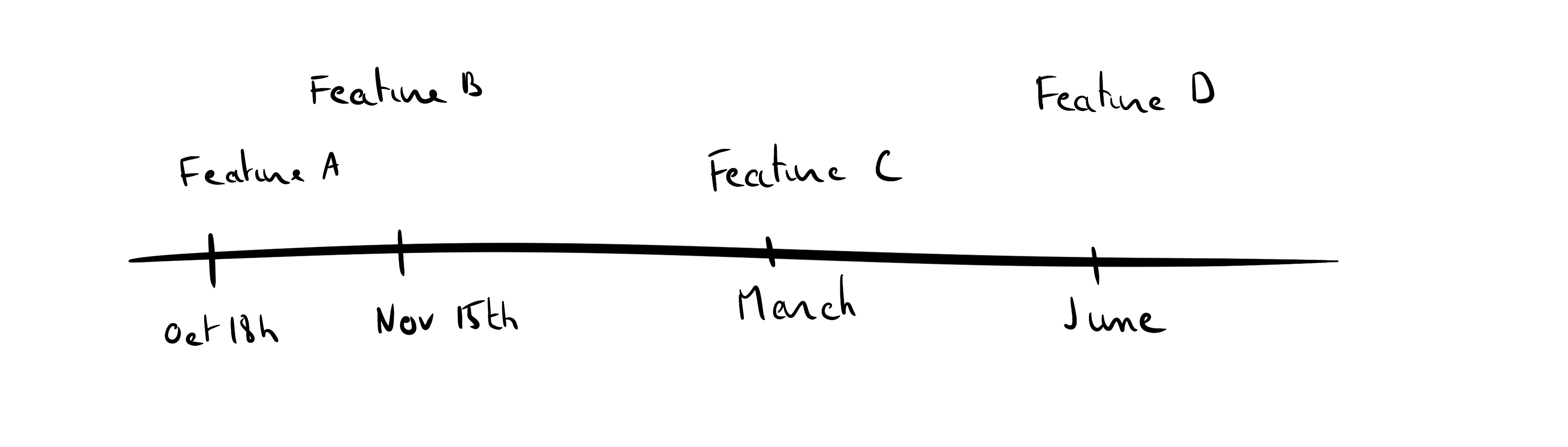

Many teams use a representation in the form of a long list of functionalities, with their completion dates on a horizontal axis.

This is the perfect tool for project-oriented teams, but it's a far cry from what the best product teams use.

As mentioned above, it's very presumptuous to think of predicting revenue impacts from a list of annual features, and it takes away any possibility for the product team to maximize its impact.

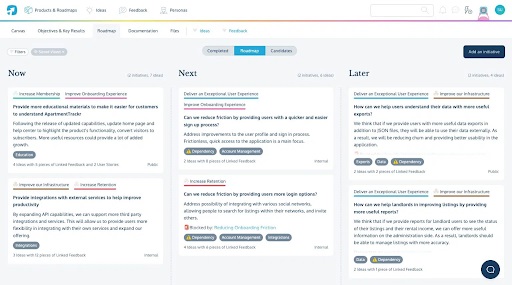

That's why there are other approaches, notably the one described by Janna Bastow which proposes replacing it with lists of objectives (OKR or other), themselves compartmentalized into three time horizons: next, now, later

Example from Janna Bastow's blog

Janna Bastow, like Marty Cagan in this video, insists that a roadmap remains necessary and is an indispensable communication tool that needs to be built. It's the materialization of the product strategy. However, it shouldn't be a list of features with release dates, but a list of objectives, with time horizons.

To anticipate the question, yes, it's possible to have an objective in Later to which you've already attached a set of initiatives. This is an extract from your "Opportunity Tree".

Example:

- Objective: Increase user acquisition by 20% by building on the existing base through virality.

- initiatives:

- develop a referral program

- partner with influencers on social networks

- develop affiliation programs

But unlike a roadmap that would list these features, these "Later" initiatives can be modified or deleted, and others can be added to meet the same objective.

The objective itself may be out of date in 12 months' time.

If you're in Continuous Discovery mode (https://www.amazon.com/Continuous-Discovery-Habits-Discover-Products/dp/1736633309?), you'll be testing hypotheses over the coming months to validate the relevance of this or that objective, and this or that initiative.

A Product Leader will have two very important challenges to manage here:

- You need to be able to detail your now next later strategy, giving time horizons while avoiding committing to a list of features. This is much more difficult than you might think. Within an Engineering team, and across the company as a whole, it's easier to talk about the future launch of feature F than it is to fulfill the O objective.

- Some people in your company will sometimes push for a firm commitment to initiatives listed in your Now Next Later plan.

Having a roadmap completely built around firm commitments for different internal decision-makers is what characterizes a feature team (as opposed to an impact team). It's limiting in terms of impact, but it doesn't guarantee success for the business.

Are dates bad?

The product teams with the greatest impact work with continuous discovery and don't use roadmaps based on lists of features associated with dates.

But does this mean that all dates are bad?

That would be a gross oversimplification.

First of all, a product strategy is based on time horizons. These time horizons are defined by the company's business imperatives.

For example, solving the problem of acquiring new users in the next 3 months may be vital for the company. There is a strong time constraint here.

As a Product Leader, you need to be constantly aware of these external constraints. You have to seek out this information if it's not available, in order to understand the company's business challenges.

Secondly, a specific product initiative can be linked to a more global strategy. When we define objectives (OKRs, for example) at company level, we are coordinating a joint effort (sales, marketing, product, customer support, etc.) in a given direction and within a given timeframe. The absence of temporality means the absence of coordination.

Temporality is a constraint, and as I said in a previous chapter, constraints are beneficial for stimulating innovation.

To quote an excerpt from the book Rework that I already mentioned in this post

Send people home at 5

When people have something to do at home, they get down to business. They get their work done at the office because they have somewhere else to be. They find ways to be more efficient because they have to. They need to pick up the kids or get to choir practice. So they use their time wisely

A time horizon is the guarantee that we know how to set objectives and find solutions to achieve them in a timeframe compatible with the company's business and the team's health.

To be more concrete, thinking that using a kanban board and prioritizing as you go is an effective product management method is probably one of the most common mistakes I see. It's a great project management tool, but never a product management tool.

What about estimates?

As mentioned above, knowing exactly how much time you'll need to spend on a future development is very expensive. To caricaturize, this is only possible by carrying out the development and then redoing it.

The exercise is therefore feasible, but at a high cost. It's this cost that we're going to try to limit with the following points.

TIP

Note that there is a direct relationship between the shortcuts taken to make this prediction and its quality. The question is, what margin of error are you willing to accept?

Now, Next, Later

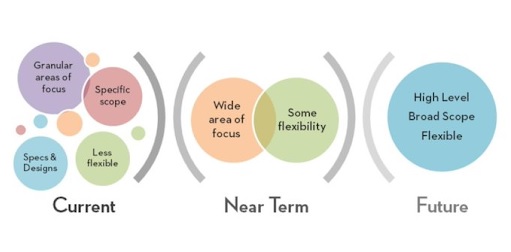

The "Now, Next, Later" framework we saw above can be used to group opportunities, to be explored according to 3 main groups:

- now: what's currently underway

- next: what we plan to do next

- later: what could be done afterwards

And what we're certainly not going to do is try to define each medium and long term item in detail to estimate the time to spend on it.

The aim is to detail precisely only what is close in time. Technology can change, and objectives can be redefined. Defining exactly how much time will be spent in 12 months' time on goal X makes no sense, and will certainly be a waste of time.

In "Now", on the other hand, we'll have worked on mock-ups, prototypes and the definition of workflows.

From Janna Bastow's blog

Finding proxies

Estimation is a sensitive subject, and not one on which everyone agrees. I'm not sure if I can say that all efficient teams use this or that approach. For my part, I'm rather close to the noestimates movement, in the sense that I don't do any poker-planning sessions to size up the work to be done down to the last task.

However, this approach is often associated with Kanban. And as I mentioned above, it's a project management method, not a product management method. Prioritizing, anticipating and planning are still necessary, without having to spend 4 hours on sprint planning every two weeks! (Yes, I've been there)

So I use three methods:

- I stay at the highest level of detail, such as the user story. There's no point in estimating anything finer than that.

- I look for a proxy that allows me to compare one element with another.

- I build up a reference frame for comparison

For example, I can estimate that the complexity of a task A is equivalent to that of a task B that I've carried out in the past.

Or, when I modify a component for a technological improvement, I can look at the size of this component and compare it with a component of the same size.

Of course, this method has its limitations:

- You need to have already carried out similar projects to be able to use these comparisons. But you can rely on comparisons made at another company.

- the proxy will always be imperfect, so there will be a greater or lesser margin of error.

I mentioned the breakdown above. This breakdown will be influenced by my working method.

If feature A can be broken down into user stories B, C and D. I would divide these user stories up in such a way as to ensure that they are relatively close in complexity and therefore take the same amount of time.

In Now, I'll have a fine-grained breakdown. This will not be the case in Next and Later.

Total time is the sum of the number of user stories multiplied by the average time spent on a user story. And I don't care if it's wrong at the level of a user story. What I'm interested in is a global estimate.

In Next and Later, I won't make this breakdown, or else it'll be very rough. But it will be enough to compare them with other projects done in the past, for example on perceived complexity.

Estimating complexity is above all a means of clarification.

While I don't advocate wasting time on precise estimates, I do believe that opening up the debate on the complexity of an initiative is necessary. Every Product leader has experienced those moments when two very senior people have radically different time estimates for a given initiative.

In discussion, these two people come to understand that it's a difference in understanding of the initial problem.

Stability and dependencies

When a team remains stable over time, it benefits from better cohesion, can initiate continuous improvement projects and acquires a better knowledge of the product. And for all these reasons, the team will also be more precise in its ability to compare and therefore estimate the work to be done.

As far as dependencies are concerned, the more they are numerous, the more the time spent on a task can vary significantly. A dependency is, for example, the fact of relying on another team to work on an objective.

That's why we try as much as possible to work with a multi-disciplinary team, so as not to depend on another team.

Out with the front and back teams, for example. Or project-based teams.

On the other hand, and this is deliberately provocative, don't be afraid of silos.

Silos enable teams to move fast. The greatest difficulty is to build these silos to enable them to be autonomous, hence the multidisciplinarity mentioned above.

The second difficulty is to be able to provide them with the necessary context for good alignment, but that's not the subject of this chapter.

Questions

Do you have a roadmap that reflects your strategy?

What form does your roadmap take?

Do you do task-based estimating sessions for each sprint?

If so, what is the time spent on the exercise versus the sprint time, and do you find that it brings value?

Resources

- Impact teams vs feature teams

- The Standish Group report on project failures

- now next later Roadmaps

- Janna Bastow on roadmap and the follow up blog post

- Marty Cagan on roadmap

TIP

This blog post is part of the book Impactful Software Engineering. Feel free to read the other chapters.